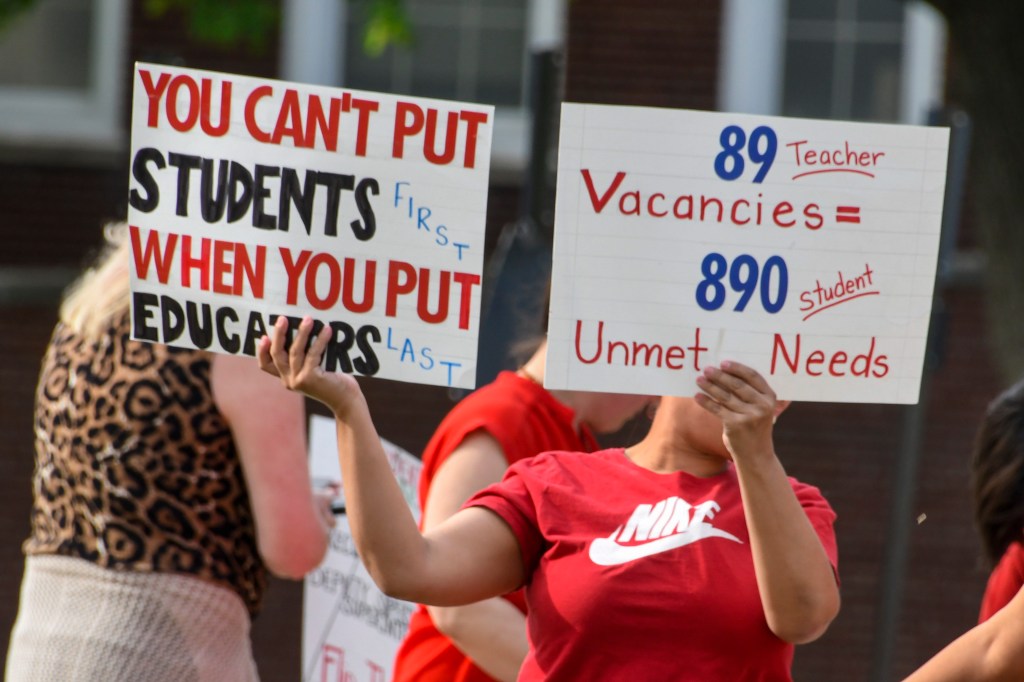

GRAND RAPIDS, MI — More than three dozen Grand Rapids Public Schools (GRPS) teachers and union members gathered outside the district’s main office at 1331 Martin Luther King Jr. Street SE Monday evening, ahead of the school board meeting, calling for a fair contract, stronger collective bargaining rights, and improved classroom conditions. Their current contract expires in June, and negotiations with the district have hit a wall on key issues.

“We’re in a staffing crisis,” said Tim Russ, Unit Service Director with the Michigan Education Association (MEA), who has represented GRPS educators for years. “There are over 100 classrooms being filled by individuals who are not certified teachers. Some only meet the state’s bare minimum requirement for substitutes—60 college credits—and the district doesn’t even budget to fully staff every classroom.”

Educators and union leaders from the Grand Rapids Education Association (GREA) are pressing for increased starting salaries to help attract and retain qualified teachers. Currently, GRPS teachers start at $44,916 a year—well below nearby districts. Forest Hills Public Schools, for example, recently ratified a contract bringing starting salaries up to $51,000.

“That’s nearly a $6,000 difference right off the bat,” Russ noted. “We wonder why we can’t fill positions in Grand Rapids.”

But pay is just one part of a broader push to address inequities in the district—particularly when it comes to access to art, music, physical education, and world languages. Some GRPS schools, according to GREA, barely receive these specialized classes because the limited number of instructors are often pulled to serve as substitutes elsewhere. Meanwhile, magnet and theme schools in the same district receive these classes multiple times per week.

“All of our suburban competitors offer four to five hours a week of specialized instruction,” Russ said. “We’re asking for equity, not luxury.”

Teachers have also been pushing the district to respond to a major legal shift that returned key bargaining topics to the table. In 2012, Michigan lawmakers banned collective bargaining over issues like teacher evaluations, discipline, and placement. That ban was repealed in 2023, restoring those rights to educators. Since February 2024, the union has been working to incorporate those provisions into the new contract—but says progress has been slow and frustrating.

“The district agreed to biennial evaluations,” Russ explained, “but they still want full control over when to put a teacher on an Individual Development Plan (IDP), which is essentially a formal warning that you’re not doing your job. There’s no accountability or fairness in that system.”

Jayne Niemann, vice president of GREA, said the current evaluation system heavily relies on standardized test scores, often disregarding the challenging realities faced by students.

“I had a student who couldn’t test because he was in crisis over a serious family issue,” Niemann said. “Others are falling asleep during tests because they wake up at 4 a.m. to catch the bus. And yet, those are the scores being used to judge my effectiveness as a teacher.”

Beyond the classroom, educators are also calling for more say in school-level leadership decisions and a return of the “right to home”—the ability for experienced teachers to return to buildings where they’ve taught and built strong relationships.

“Many building leaders don’t have classroom experience,” Niemann added. “Teachers are being micromanaged and disrespected by people who don’t understand what we do every day.”

Meanwhile, the district’s latest proposal includes only a 1.5% salary increase for teachers—significantly less than the 3% raise granted to other employee groups. Union leaders argue this offer is being used as leverage to push through evaluation and placement language that educators find unacceptable.

“They’re holding our raise hostage,” Russ said. “We already had a 1.5% increase from three years ago. The district is now tying the additional 1.5% to language that limits our rights on evaluations and teacher placement—topics we just got back the right to negotiate.”

The frustration is palpable among GRPS educators, many of whom say they’re sacrificing their financial futures and retirement security to serve students in a district with high needs—and little support.

“What’s the incentive to stay?” Niemann asked. “We’re working with kids who experience trauma, poverty, and daily challenges. We’re not asking for more than what other districts are getting—we’re asking to be treated like professionals. If you can’t pay teachers fairly, at least give them back their rights and some dignity.”

The GREA’s top demand at this stage is open bargaining—a transparent process that would allow the public to observe contract negotiations in real time.

“Our number one ask of the school board is simple,” Russ said. “Let the public see what’s happening. We believe that if the community could watch these negotiations unfold, they’d understand exactly why we’re standing out here demanding change.”

With the June deadline approaching and no deal in sight, Grand Rapids educators say they are prepared to keep raising their voices—until they are truly heard.